Very often in the West we hear the question: how much caffeine does a kind of tea have? I am afraid to say that, at least in tea, this can never be a straightforward answer, unless you chemically analyse the cup of tea each time you are drinking it.

Caffeine is a stimulant that belongs to the methylxanthine group. It used to be called “theine” in tea, but actually it is the same molecule that is present in coffee. Why is it so difficult to determine the caffeine ingestion and its effects, when talking about tea? There are several factors to consider.

One factor is the type of plant used. Even if tea is made mainly from the same plant species – Camellia sinensis, there are several different varieties and cultivars. Caffeine can be found in different amounts, depending on the exact plant we are using. Therefore, a tea plant in Japan can have different amounts of caffeine from a tea plant in China. But also a tea plant in a specific tea field in Japan can have a different amount of caffeine from a tea plant in a neighbor tea field.

The other factor is what part of the plant are we using to make the tea. Generally speaking, high grade teas are made from buds and youngest leaves. Those are the parts that usually have higher caffeine content. Nature is wise: buds and young leaves are tender, full of flavor and nutrients – insects are attracted to them the most, and the plant uses caffeine, which tastes bitter, to protect itself. For a similar reason, the harvesting season can also affect the caffeine content.

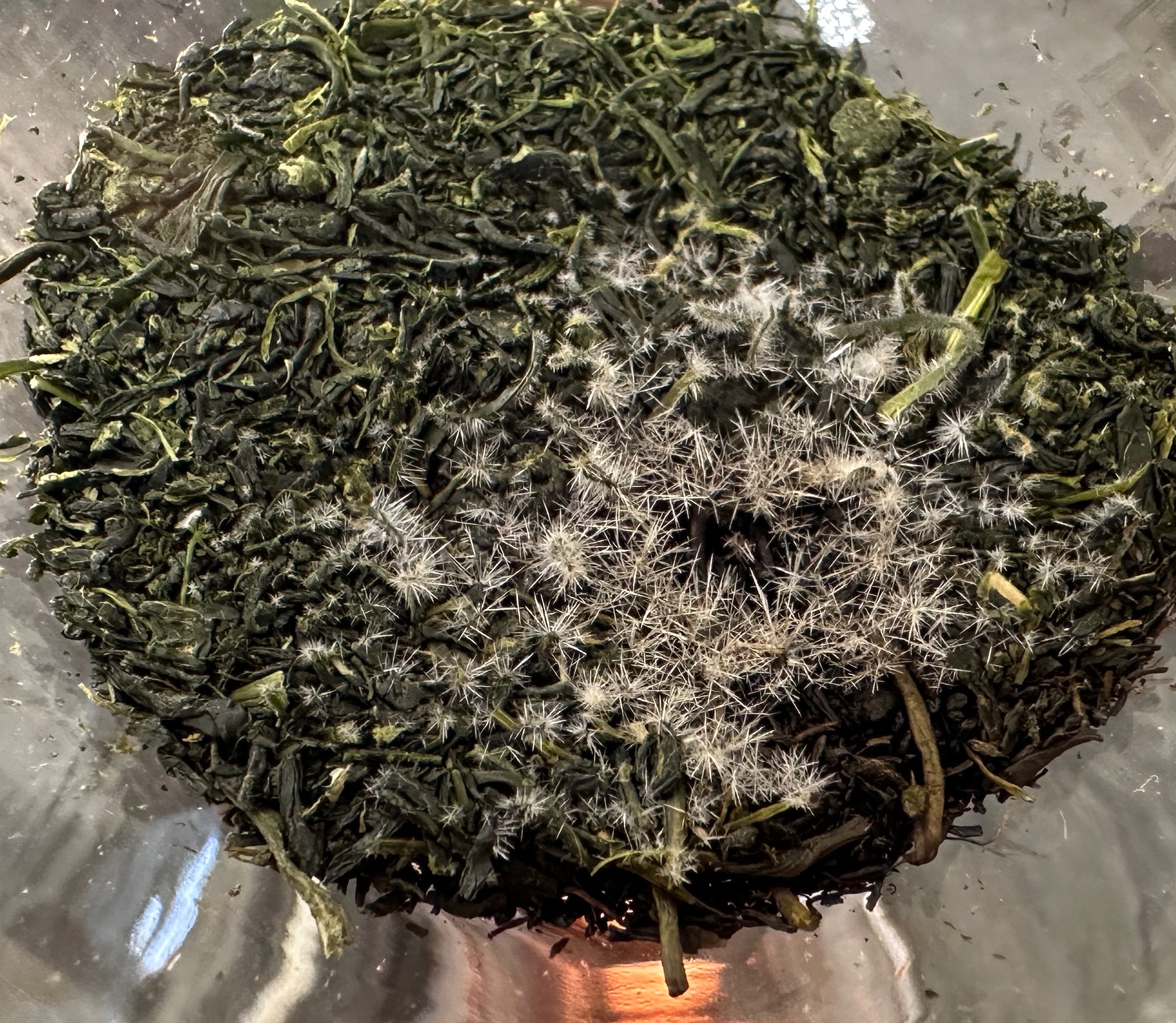

Then processing comes into play. Many times we have read claims about the roasting process of tea being responsible for lowering the caffeine content in the final tea. That is also not entirely correct, nor something very easy to draw conclusions to. When tea leaves are subjected to direct and strong heat, caffeine can melt and evaporate. Once it cools down on a surface, it can be seen in a form of crystals (like the photo of this article). Images of tea factories that roast tea, with caffeine crystals on the ceiling, are often shown to backup this theory. The fact is that actually caffeine is quite heat-resistant and only melts at 227ºC. Therefore, when we roast tea leaves, it really depends on what machinery we are using and at what temperature (and probably for how long). Although we cannot speak about other countries and their tea processing styles and techniques, in Japan the roasting process is typically done using a drum roasting machine. We need to note, that the temperature to which the machine is set, will always be higher than the actual temperature the tea leaves reach when touching the drum surface. Moreover, the leaves keep on moving inside the drum. So if the temperature is set at 200ºC, for example (common for hojicha), you cannot say that the tea leaves reach such a high temperature. Also, roasted Japanese tea is not a one single specific tea with a fixed recipe to follow – each tea producer can roast the tea according to their experience or preference. While some could indeed roast strongly enough to make some caffeine evaporate out of the leaves, many others do not. The main reason why roasted teas are usually considered lower in caffeine, is because the material used for hojicha, is usually bigger leaves or stems – that contain less caffeine from the start. Therefore, we can say that usually hojicha is low in caffeine content, but it still does contain caffeine. How much? It is impossible to generalise.

Another very important factor is the actual tea brewing. The extraction of caffeine to water depends on steeping temperature and time. The higher the water temperature, the higher the percentage of caffeine is extracted. The longer you leave it steep, the more caffeine is released into the brew. Another claim we have seen a few times is that cold brew has no (or lower amount of) caffeine – but cold brew usually is left for many hours, even overnight. So it will also have some caffeine. Moreover, if we talk about powdered tea, then, it is also different: when you drink matcha, you actually ingest the whole leaf. So you are definitely drinking all the caffeine content of that tea in one go. The effect can easily be stronger compared to brewing loose leaf tea.

There is one more essential characteristic of Japanese teas that is a quite important factor to consider: L-Theanine! This component is an amino acid that can be found in tea, and is responsible for the relaxing effect that tea has on our brain. Tea can keep us awake thanks to the stimulating effect of caffeine, but at the same time it relaxes us down thanks to the theanine effect. It is also important to consider the way theanine interacts with caffeine, and how our bodies digest them – this also make a difference. The effect of caffeine is faster when drinking coffee. When drinking tea, our bodies first need to separate the theanine molecule from the caffeine one to process them. Therefore the effect is more gradual and longer lasting.

Finally, each person is also different, and not every day is the same. Two different people can have different sensitivity to caffeine. Also what time of the day are you having the tea? Is your stomach empty or full? Are you well hydrated? Those factors can play a role on how strongly we will feel the effect of caffeine. It can be stronger, even making you feel dizzy, if you consume caffeine on an empty stomach.

We hope this article has helped to clarify some points about caffeine without confusing you even more. My conclusion to the caffeine debate is: there is no straight answer. In future we might discover more, or may even have more ways to analyse what is in our tea, right at home. Studies on caffeine can shed new light in years to come. In the meantime, try to learn from each tea and from your own body.

2 thoughts on “Caffeine in Japanese Teas”

Thank you for this article on caffeine in tea! I didn’t know about the evaporation point of caffeine, and never actually thought about the reason why hojicha has less caffeine.

About brewing the tea, often I read that if you want to decaffeinate your tea you can discard the first brew, but is it actually true? How long do you have to brew it? I’m reticent to doing it because I’m afraid the tea will lose some of its flavor.

Thank you for your comment, Sandra.

With discarding the first brew in Japanese teas, you’d definitely discard some caffeine. But again it is hard to determine how much. If you brew at high temperature, you would discard more. But then, you most definitely also lose a lot of flavour. As Japanese teas are usually straight in shape, they tend to release the flavour (and components) quite fast in the water.