Contents

Do you know Wakōcha?

Speaking about Japanese tea we cannot help but recall in our mind the refreshing flavor of Sencha as well as the toasty aroma of Hōjicha, not to mention the creamy texture of matcha, all different types of green tea.

In recent years, due to their fascinating cultural background as well as their well-known health benefits, Japanese green teas, and matcha, in particular, have become very popular and appreciated among an ever-increasing number of consumers all over the world. Yet, as the majority of tea enthusiasts already know, a part of the Japanese tea industry (though small compared to green tea) is made up of black tea.

The term Wakōcha (和紅茶), literally Japanese Black Tea, refers to black tea produced from tea gardens in various tea production areas of Japan. Although the black tea consumed in Japan is mostly imported, the production of Japanese black tea has gradually increased (more than 200 tons produced in 2016), and the success and reputation obtained give hope for even greater development of the production in the future. In this article, we will discuss the origins and developments of this less-known Japanese tea industry as well as the characteristics that make Wakōcha unique in the broadest overview of black teas.

The origins of Japanese Black Tea

1875 ⇒ 2020

Japan’s history of black tea production is made up of many ups and downs, bearing periods of great success on the market soon followed by periods of crisis.

Considering the whole history of tea in Japan, the beginning of a Japanese black tea industry is very recent. Its origins date back to the eighth year of the Meiji era (1875), while in the previous Edo era Japanese didn’t even know the existence of black tea.

In those days, despite Japan’s efforts, the yield of green tea as an export good was not very successful, having to face the high demand for black tea in the western market as well as other’s countries’ competitiveness. Thus, focusing on the demand of the occidental countries, and willing to create its very own production, Japan’s government invited expert farmers from China and issued the “Black Tea Process Record” (紅茶製法書) to spread the acquired knowledge.

Following those guidelines and using the tea plants that grow wild in the mountains around the prefectures of Ōita and Kumamoto, local tea producers were encouraged to acquire the skills for black tea’s specific manufacturing method. This was the very first beginning of black tea production in Japan.

In the following year (1876), the government sent a Japanese delegation lead by the tea farmer Tada Motokichi to the Indian regions of Assam and Darjeeling, and to Ceylon to gain a better understanding of the production process. The delegation brought back seeds of the Assamica variety of Camellia Sinensis, which started to be cultivated all over the country and then crossbred to find a match for the Japanese climate.

In 1878 a “Black Tea Manufacturing Training Regulation” (紅茶製造伝習規制) was established by the government to prevent the overproduction of poor quality black tea, and the Chinese manufacture method was definitively set aside. As a result, the attempt to establish a crop in the area of Kōchi province, using the Indian manufacturing process, was successful, and the first batch of Japanese black tea was exported, gaining a good evaluation on the British market. Various training centers were established in Tokyo, Shizuoka, Fukuoka, and Kagoshima.

In 1887 imported black tea was introduced, and the Japanese black tea industry began to follow an irregular trend, influenced by the course of historical events (First Sino-Japanese War and the beginning of Japanese colonialism in Taiwan, the First Great War). Following the Great War, a great quantity of domestic black tea was dispatched in Europe and England, obtaining a reputation equal to, if not higher, than that of other countries; the peak was reached after the end of WWII, in 1954, when over 5000 tons were exported. In those years was officially registered the very first Japanese tea cultivar (茶農林1号), named Benihomare, and selected from the seeds of the tea trees brought from India by Tada Motokichi. It was also the first Japanese black tea cultivar and is still used today for the production of Wakōcha.

By 1963 fourteen new plants were registered as superior varieties by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (農林水産省). Meanwhile, the production of black tea in other countries expanded, and as their product’s price-quality ratio reached a better scale compared to that of Japan’s, the exports of the country started to decrease. The high economic growth caused the cost of black tea production to increase significantly and Japan gradually lost its competitiveness on the market. After 1970 the production of Japanese black tea almost stopped while imports of black tea from other countries expanded rapidly. The increased use of tea bags and the launch of black tea in plastic bottles culminated in the first Japanese Tea Boom (1997) when black tea imports reached nearly 20000 tons.

Despite the situation, technological development in manufacturing techniques and the research on new tea species did not stop so that in 1993 the newest black tea variety, the Benifūki, was registered. Finally, also driven by black tea’s success in the country, in 2002 the domestic production saw a new revival, and the same year, the researcher Akasu Jirō created the term “Wakōcha”. Recent studies on the health benefits of the Benifūki variety contributed to the expansion of different kinds of black tea. In 2016 more than 200 tons were produced and we can say that Japanese black tea finally regained its reputation not just locally but amongst many tea connoisseurs all over the World.

How is Japanese Black Tea produced?

Withering ⇒ Bruising/Crushing ⇒ Full Oxidation ⇒ Drying

Black teas are fully oxidized teas. In Japan, the leaves for making black tea are mainly harvested by machine, usually around May and July. Following the first spring harvest, the second harvest or second flush produces the so-called Nibancha teas. The late harvested tea leaves have a higher content of polyphenols (tannins), thus being more suitable to produce tea with a certain degree of astringency and bitterness.

Once plucked, the enzymes contained inside the leaves start to break down in contact with oxygen, heat, and humidity, causing a chemical reaction that darkens the leaves. The process for black tea takes longer compared to that of green teas: while to produce green teas the oxidation process is immediately stopped with heat in the so-called “fixing” stage (such as for Japanese green teas, whose leaves are mostly steamed), to produce black tea is necessary to increase the quantity and type of flavor elements. To achieve this result the leaves are left to wither from a minimum of 10 to a maximum of 15 hours so that the amount of moisture is reduced up to 60%. The procedure makes the leaves soft and easy to process in the following step, called “bruising” or “crushing”, whose purpose is to stimulate and enhance the oxidation process.

In the black tea industry, there are two procedures: the CTC (crush, tear, curl) method and the orthodox method. In the first case, the leaves are mechanically chopped and crushed using various types of rollers, and eventually made into very small granules. Instead, the orthodox method requires a process of light crushing and rolling that allows the essential oils contained in the leaves to spread out, creating the tea’s characteristic aromatic notes. The rolling also gives the leaves a twisted shape.

The leaves are then left to oxidize completely and the whole procedure is concluded with a final drying stage that ultimately arrests the oxidation. To avoid the growth of harmful molds, the drying is carried out until the residual moisture content isn’t exceeding 3%. At the end of the whole process, the final product is roughly one-quarter of the weight of the raw leaves.

In CTC, the resulting fragments of dried leaves are sorted according to their size in various grades, like fannings and dust, mainly used for tea bags, while orthodox teas are divided into “whole leaf” or “broken”.

Japanese black teas are primarily produced using the orthodox method, and the grades go from OP (orange pekoe) to broken. Besides, to maintain a standard and meet the demands of consumers, the majority of black teas put on the market by the various companies are not single origins, but blends from different producers and varieties.

Another crucial factor worth mentioning that contributes to the quality and taste of the finished product is the difference in the care of the tea gardens between those intended for green tea and those for black tea. To obtain the sweet and umami taste of green teas, tea growers use to dispense nitrogenous fertilizers on the tea fields while using low amounts of pesticides to favor the development of the plant’s natural defenses. Black tea, on the contrary, requiring a strong taste with no umami, is made from gardens grown using less fertilizer, and more and more producers prefer to use natural methods avoiding the use of pesticides and favoring the spread of ecological and organic farming techniques.

Varieties, cultivars, and production areas

Japanese tea, like every other tea, is made from the leaves of Camellia sinensis (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze), an evergreen flowering plant of the family Theaceae. Tea plantations in Japan are mainly intended for the production of green tea, although theoretically, the same leaves can produce every kind of tea. The substantial difference lies, as we have seen, in the manufacturing process, but it is also enormously determined by the variety of the tea plant and its specific characteristics.

Camellia Sinensis has two main varietals: Chinese (C. Sinensis var. Sinensis) and Indian (C. Sinensis var. Assamica). The vast majority of Japanese tea, including black teas, is produced from Sinensis varietals, while in the principal black tea production areas are commonly used the larger Assamica leaves. Assamica is native to the north-east Indian region and today remains principally farmed in warm and humid countries like Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and parts of Africa. Due to its longer and wider leaves and higher polyphenol contents, the fermenting process is easier and gives a stronger tea, thus being the most suitable variety for black teas. Although Assam plants were successfully cultivated in Kagoshima, to improve the quality of production and create a crop more adaptive to the Japanese climate, the farmers developed new cultivars by artificially crossing Assam and Sinensis varietals. The temperate weather is more favorable for the cultivation of the Sinensis species, more resistant to cold than Assamica, and in Japan the refined breeding allowed the quality of the harvests to improve drastically. However, since the consumption of tea in Japan is based principally on green tea, the farmers continued to focus their efforts on the cultivation of Chinese varieties, which give a mellower and less astringent tea. An example is Yabukita (茶農林6号), born in Shizuoka in the early twentieth century, and nowadays the most widespread cultivar in Japan, representing up to 75% of green tea production. The use of varietals mainly intended for green tea production results in black teas with a taste smoother than its Assamica counterpart, and that’s why many producers prefer to use hybrids to create black tea with a more robust flavor. Although still pretty rare compared to the teas from Sinensis varieties, it’s possible to find black teas produced from Assamica breeds like Benihomare or Benifūki (created from Benihomare and Darjeeling indigenous species).

Tasting notes

The aroma and taste of each “single origin” tea depend of course on many factors such as climate, type of cultivar, terroir, growing techniques, harvest season, but generally speaking, some of the characteristic traits we most commonly find in Japanese black teas are:

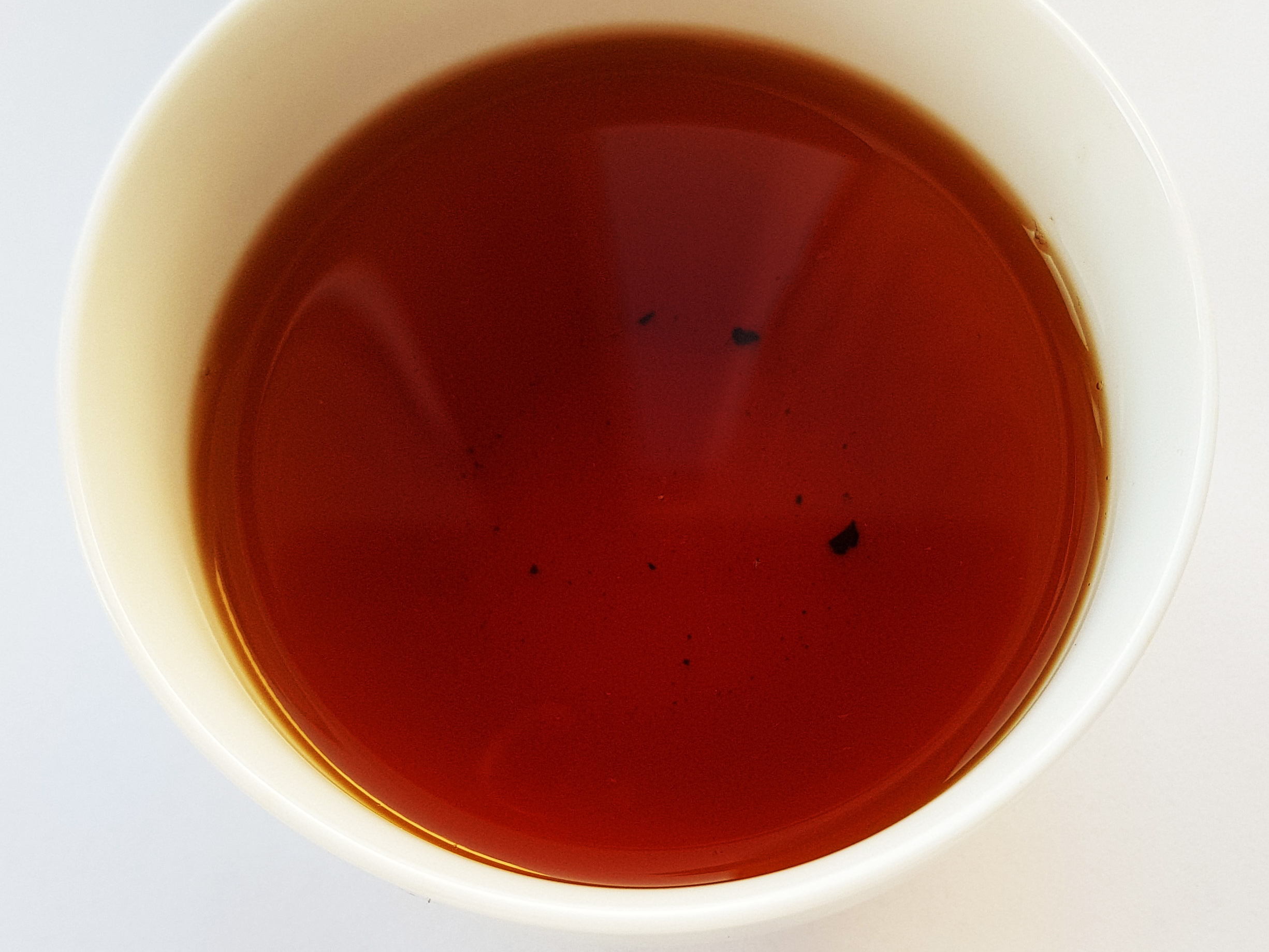

liquor: usually clear, with a color between desaturated orange and reddish-brown

taste: low astringency and bitterness, brisk feeling in the mouth, smooth texture

aroma: slightly malty, floral, spicy, hints of sour fruits.

As an example, I’m going to present you the results of the tasting of four black teas from different gardens: two black teas from Yabukita crops of different regions, one Benifūki and one Kanaya Midori (茶農林30号), a cross between Shizuoka Zairai (old indigenous tea trees) and Yabukita.

Shizuoka, Fujieda

Harvest: Spring 2020

Variety: Yabukita

Dry leaves: sweet and flowery, with hints of cherry, prunes, and spicy wood

Wet leaves: malt and molasses with delicates floral notes

Liquor: On the nose, the aroma is intense, with sweet and fragrant fruity notes of plum and caramel, accompanied by slightly pungent hints of licorice; on the mouth, the liquor is brisk and have a full-bodied taste with a well-balanced astringency, and a non-persistent bitter final; the aftertaste is malty and sweet with hints of plum, bitter almonds, and cherry flowers.

Shiga, Asamiya

Harvest: Ichibancha (first harvest of the year) 2020

Variety: Benifūki

Dry leaves: flowery, with fresh notes of field salad and quince

Wet leaves: green sprouts and field lettuce with delicate flowery notes

Liquor: On the nose, the aroma is gentle and refreshing, with flowery notes and a persistent frizzy aroma; on the mouth the liquor is sweet with a mellow round taste, free of astringency, and leaves a refreshing sensation along the throat; the aftertaste is flowery with fresh notes of young sprouts and fields lettuce and hints of white grapes peel.

Kumamoto, Minamata

Harvest: Late Spring 2020

Variety: Yabukita

Dry leaves: fragrant and warm woody notes, with hints of licorice root and roasted soybeans

Wet leaves: malty and woody, with a slight sourish note of yuzu

Liquor: On the nose, the aroma is sweet and fruity, with tones of plum and wildflower honey, and hints of warm roasted soybeans; on the mouth, the liquor leaves a slightly bitter finish, has a nice strong body and rich taste, and a well-balanced astringency; the aftertaste is malty, with notes of cooked sugar and prunes, and light non-persistent hints of citrus.

Kagoshima, Yakushima Island

Harvest: various (blend)

Variety: Kanaya Midori

Dry leaves: light woody aroma with delicate notes of artichoke, soy, and chestnut honey

Wet leaves: artichoke with secondary notes of bark and soy

Liquor: On the nose, the aroma is delicate and sweet, with persistent hints of artichoke and more subtle notes of green grape and spice; on the mouth, the liquor is sweet and rich, and has a full-body and well-balanced astringency; the aftertaste is slightly malty with a persistent note of artichoke.

As you can see from the examples in the tasting, the variety within Japanese tea is incredibly wide and difficult to frame in a range of attributes common to each tea. The great diversity of cultivars and the peculiarity of every single terroir create endless possibilities that could certainly intrigue and meet the taste of any tea lover.

How to Enjoy Japanese Black Tea

Unlike green teas, black tea commonly requires higher infusion temperatures and longer steeping. I have found that higher quality teas prepared using more leaves with lower temperature (90°C/195°F), and shorter steeping time, can hold up to three (sometimes even four) infusions. The usual amount of tea leaves for a 350 cc teapot is 5-6 gr. I recommend using soft water, containing low TDS, brought to 95°C (203º F). The steeping time can vary from 3 to over 5 minutes, depending on personal tastes. Some stronger Japanese blacks can also be enjoyed with milk. These guidelines are based on my personal preferences, and experience on the performance of the teas I’ve had the opportunity to try so far. Hence, I leave you the last word whether these parameters are valid or not for the tea you are going to taste.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we can say that Japanese black tea represents the most striking example of how the tea industry in Japan, although still strongly associated with the production of green tea, is anything but fossilized. On the contrary, the continuous exploration for new market opportunities to satisfy a more and more exigent audience of consumers, both at home and abroad, together with the development of farming techniques more attentive to the environment and the ecosystem, makes us look with curiosity to the future development. It will not be a surprise if, in the years to come, we will hear more and more about Japanese black tea, managing to find unusual new specialties on the market.

*The article was written by our Tea Fellow Sara Cherchi. You can follow Sara on her instagram page.

*Photo credit: Sara Cherchi

2 thoughts on “Japanese Black Tea – Wakoucha (和紅茶)”

Thanks for the nice article (and all the research and tea drinking to be able to write it!!)

Thanks for the updated nice article for the tea lovers.